Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

First, an important announcement:

In case you missed it: Fu’ad wrote and published his last Naira Life story last week. My name is Toheeb, and I’ll be taking over from him.

Also, I had an interesting conversation with him where he talked about the origin of Naira Life and his experiences writing the first 100 episodes. You can read it here. It will give you an idea of what we’ve been trying to do with this series.

Anyway, this is cheers to change and new beginnings.

Now let’s get this party started.

Talent and promotion are two different beasts in the music business. The subject of this week’s story, an up-and-coming artist knows this better than most people. So, how does he earn money in an industry where nothing is guaranteed, and what does his #NairaLife look like?

Tell me about your first memory of money.

I grew up in a house crawling with kids in Benue State, and money was the prize for good behaviour. Every time I got good grades, my dad rewarded me with money. Also, If I was on the good side of any of my father’s wives and they thought I behaved well, they tipped me.

How many wives did your dad have?

Four wives. My mum was the first and had seven kids for him. I’m the sixth. My parents got divorced when I was four and my dad got custody of the kids. My mum checked in on us when she could, but she was always on the road because of her business.

What was it like growing up though?

When you live in a home filled with children, you learn how to compete for resources. You have to be strong. Living that reality — even though it wasn’t always ideal — showed me where hustle ranked in the grand scheme of things.

Do you remember the first thing you ever did for money?

When I was about to get into secondary school in 2005, my dad wasn’t ready to take care of the fees. So at 10 years old, I started going into the bush to fetch firewood and sell to people. I raised the fees and enrolled myself in school.

I sold a bundle for ₦30 or ₦50, depending on who the buyer was. On a very good day, I got up to ₦100 on a bundle.

Wait, how much was your school fees?

₦150 per term.

Omo.

I don’t hold it against my dad actually. He had a lot of responsibilities. For four years, I stuck with the firewood thing, and my mum and older siblings chipped in when they could.

And then?

I left the village. I had a sister who lived in Abuja, and she thought it was best if I came to live with her. In 2009 and at 13, I moved to Abuja. Coming out of the village was a dream, but it was also a lot. I had to adjust to having smart people around me all the time — no shade to my classmates in the village. When I got the hang of the city and my new school, I realised that I had been handed a lifeline. My sister took care of my education and pretty much everything else, and my mum also contributed. Not much happened in the remaining years I spent at secondary school.

I guess university came next.

Yes. In 2012, I was admitted to study at a university in the south-west. My mum had passed away at this point. She died when I was in SS3.

I’m so sorry.

It’s fine. My sister continued paying my tuition. Every now and then, she sent me an allowance. ₦10,000 this month, ₦15,000 the next month. On my part, I went to uni with a mindset that I was becoming my own person. I started looking for things I could do to make extra money.

What did you decide to do to make this happen?

Modelling. I had the physical appearance for it. I started going for auditions in my first year.

How much did you get from a gig?

On average, I got ₦5,000 per gig. This was in 100 level and didn’t have a lot to worry about, so I was living fine.

What was the highest amount you got from a gig while in school?

₦50,000 from a fashion show I went to in 2015. However, only ₦30,000 came to me. The guy who helped me secure the job got ₦20,000.

Anyway, when the money from modelling became more frequent, I decided that it was time to turn to something I had always wanted to do.

What was that?

Music.

When did you know you wanted to do music?

I’d always known I could sing. But I wasn’t sure that I wanted to do it professionally. I just wanted to put something out. I did that in my second year at uni when I recorded and released my first song.

Do you remember how much you spent putting the song out?

I spent ₦5,000 on the studio session. The cover art took ₦3,000. I didn’t know as much as I do now about music promotion, so I didn’t do a lot of that. I paid ₦1,500 to host it on a blog in school. One of my lecturers heard the song and liked it so much that he offered to pay for the video. It cost ₦30,000.

I was like, “Omo, I go run this thing.” I got a manager and started doing it professionally.

Did you make anything off the song?

Not from streaming, no. But I was invited to perform at dinner parties and other events in school because of that song. I don’t remember how much I made from each performance or how many of those things I went to, but it was between ₦3,000 and ₦5,000.

The best thing about that time was the platform. Brands used to organise events, and although they brought their artists with them, they also needed local acts, preferably student artists. I was one of those chosen for this, and it brought in extra cash.

What happened after?

I leveraged the relationships I had with people to build a structure around my brand. People offered to manage me. Someone volunteered to be my road manager when I went on shows. Producers wanted to produce songs for free. I put out two more songs before I left uni. For NYSC, I was posted to a state in the north, but I relocated to the south-west. Before NYSC ended, I got another manager, and we agreed he would take 30% of whatever I made. In 2018, he got me my first major gig post-uni.

What was the gig about?

Performing at a lounge in Port Harcourt. I worked on wednesday and saturday nights and got ₦60,000 per month. I also got tips. On nights when their guests felt generous and thought I was doing a good job, they came on-stage to spray me money.

I started getting invited to a couple of other shows. ₦50k here. ₦60k there. While I was doing all this, I put out another song. It was the first time I pushed a song with a plan. I got it to play on the radio and made a video. The video alone took about ₦150,000.

I also clocked something that year.

What was that?

It’s almost impossible to convince people to pay money or even give an artist on the come up a chance. The mechanics of demand and supply can be harsh. There was this time I was supposed to perform at a show. My name was on the performance list but nobody called me to perform. When I tried to make an issue of it, they told me that they only brought out artists people wanted to see. That opened my eyes.

Ouch.

It was pretty dampening. But everyone has their story and we can’t all make it overnight. I just took it as one of those things that comes with the struggle and kept pushing. I still am pushing.

How were you financing your moves as an independent artist?

My manager was a little buoyant, and he believed so much in my craft. We didn’t have a written agreement, but he was willing to put in resources to get me out there. It was a bit of everything coming together to make it work. Also, I discovered songwriting and how it’s a hidden gold mine.

What do you mean?

It happened like this: I went to a studio in 2019 to record a song. A popular artist was there, vibed with the song and asked that I give him the song for a fee. He paid me ₦150,000 for it. I wrote one or two more songs for him and he introduced me to a few more people, and it picked up from there. I charge between ₦100,000 and ₦300,000 to write songs for people now.

Lit.

Before then, I didn’t think the Nigerian music industry embraced the idea of songwriters.

2019 was also the year I met 2face and his team.

Flex.

You know, I’ve always been a die-hard 2face fan. He’s from my village, and we idolise him there. I’d been participating in his competitions and tagging him on my posts, hoping to meet him one day. That year, he organised another competition because he was looking for three young talents for a project he was working on. I reluctantly entered and I was picked. That was it.

Did this give you some boost or something?

I got more attention from the mainstream. A couple of record labels reached out. But the thing about signing a record label contract is that you have to be very aware. Even when I decided to go with a label, there was a lot of back and forth reviewing the clauses. It took about four months before I penned down the deal. I signed with them in November 2019.

What were the terms?

I can’t talk about the details, but they were going to give me freedom to express myself and back me financially. Talent is like 60%, money is 40%. The contract was supposed to be a relief. It was me trusting them to make me grow in ways I couldn’t do as an independent artist.

How’s it working out?

There’s been ups and down. A couple of things have happened in the past months, so it’s currently on hold. That’s the simplest way I can put it.

So, how have you been making sure money comes in?

This music business get as e be. No matter how big you are, you can’t tell how busy you will be in a week or a month. 2020 was chaos. I literally didn’t have any public performance. I made the bulk of my income from songwriting.

Do you track how much you make in a month?

I make about ₦200,000 – ₦300,000 every month. But it’s not set in stone. I’ve made ₦100,000 in a month. I’ve made ₦500,000 in another month. It depends on how the market moves.

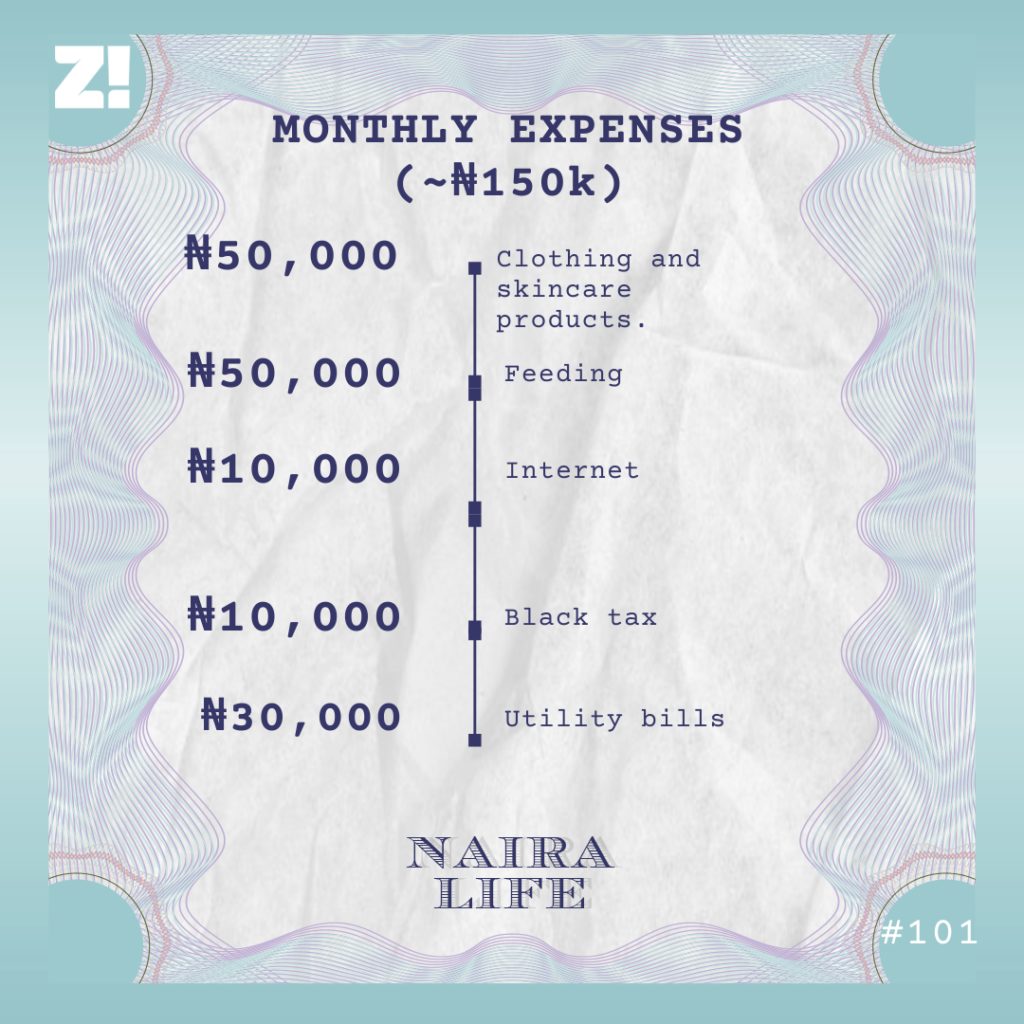

Can you break down your monthly expenses?

This definitely goes up on the month I have to pay rent. Rent is #520k

Do you have a savings plan?

I used to be about that life, but I’ve found that it’s better to invest. I put ₦400,000 in an agriculture business recently. It isn’t a lot, but it looks promising. I have other running investments too.

How much do you currently have in investments?

I don’t know. They’re everywhere. I’m not good at tracking them.

What aspect of your finances do you think you could be better at?

Bringing my investments together. At the moment, they are all over the place. I’m struggling with getting a grip and knowing where my money is and what it is currently doing.

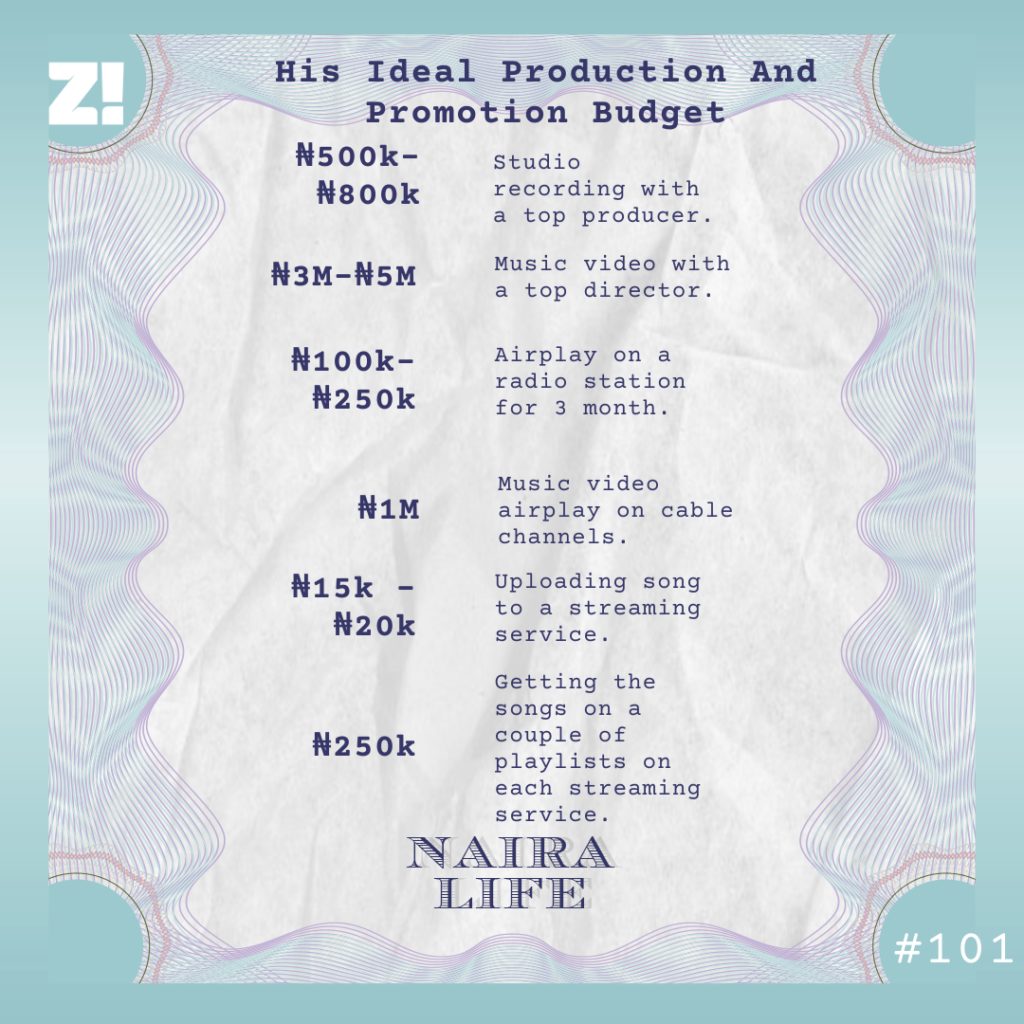

What do you want right now but can’t afford?

Omo, I can’t afford the kind of promotion I want for my music. On average, promotion costs on one song can run into ₦10,000,000.

Also, if you want social media influencers to talk about your song and sometimes get you on the trend tables, you have to distribute reasonable sums to them.

Record labels budget between ₦10,000,000 and ₦15,000,000 on a single. Some go as high as ₦20,000,000 if they want to disturb everywhere.

Bruh!

A lot of work goes into making a song. Some of us aren’t as big as we probably deserve though we have songs that can compete with the best. But promotion is a different beast. It’s sad, but it is what it is.

And this is where record labels come in. They have money and they are risk takers. But in some cases, they also have the power to rip you off when you blow. The industry is a lot. Talent isn’t enough — that’s for sure.

What’s something you bought recently that improved the quality of your life?

I spent ₦300,000 on a couple of production equipment. It’s not always easy to go to the studio to record, and not all producers get the picture of what you’re trying to do. It helps if you can do some of these things yourself. They weren’t cheap but were totally worth it.

Would you say you’ve gotten your big break yet?

Lmao. I’ve not even gotten a small break.

Lmao. On a scale of 1-10, how will you rate your financial happiness?

2. Not that I’m not content, but I always feel like there’s something more out there for me. I’m hoping my investments in agribusiness pick up the way I want. When that happens, I can move up to 5.