Every week, Zikoko seeks to understand how people move the Naira in and out of their lives. Some stories will be struggle-ish, others will be bougie. All the time, it’ll be revealing.

The subject of today’s story lived in Nigeria for a while, but he currently lives in his home country, Liberia.

Tell me about that first cash that you felt was yours.

Let me start by saying I’m the laziest person I know. When I was a kid, my dad wanted to imbibe reading as a habit into my siblings and I. So what did he do? He’d give us a reading challenge – a book – and then he’d give money to whoever finished first. I always finished first and got the money. This is where the laziness came in. Because I hated doing my laundry, I’d bribe my sisters with the money I got so that they could do my chores. Everyone was happy.

But my first real gig was teaching on holidays at a secondary school while I was in Uni. I was getting paid like ₦15-20k per month, in 2012.

Okay, post school?

Some quick context before we continue, I haven’t lived in Liberia all my life. I actually moved back here after University in 2015.

You lived in Nigeria.

Yeah. I wanted to go to Law School here in Liberia – it’s three years – but what happened was, people that were supposed to enter Law School in 2014 didn’t start till the next session in 2015.

Why?

Ebola. Everything stopped, including school. So that means that I couldn’t go to Law School immediately. I gained admission for a Masters Degree in the UK, but I couldn’t afford it. My parents couldn’t too.

So, still in Nigeria and feeling a little trapped, I applied to volunteer at an NGO. I showed up at the interview, and somehow left with a fulltime job. The gig paid ₦60k a month, and this was 2016. I worked with some of the most amazing people there. But then I left after a few months.

Something else clicked?

My Masters. My parents raised that money, somehow. After my Masters, I made up my mind to move back to Liberia. So in January of 2018, I moved back here. You want to hear something funny?

Hit me.

I celebrated one year of unemployment in January this year.

That escalated quickly. What were you doing for one year?

I’d come back to Liberia with the hopes of making a difference in my country. I was coming back as a 22-year old with two degrees. I know in Nigeria where you’re coming from, that’s pretty normal. In Liberia, it’s not. Because if you grew up in Liberia, you’re not finishing your first degree till you’re in your late twenties at best. That’s what happens when you factor in a cumulative 14 years of war.

For example, I worked as a lecturer briefly – I’ll get to that part – but most of my students were older than me.

So, it wasn’t completely rare, but you don’t just run into a 22-year-old like me everywhere you turn.

I had big prospects coming back to Liberia and making at least $600 a month, working in the government. I’ll give you context to understand this number.

I’m listening.

I almost got a job to work with the EU delegation in Liberia for a media role. I was shortlisted, but I didn’t get it. That job would have paid me $2000.

In Ellen’s government, I was more confident about getting a job. But when I came, the government had changed, and this government was employing based on party alliances. There’s a song people sing now, it’s called “In The Photo”.

What’s that?

“When they took the photo, I was there. But when the photo came out, I was not there.” Basically, people are saying ah, when you were campaigning, I was there. Now that it’s time to reap the rewards, I’m not there. People loyal to the ruling party still can’t get jobs, and they’re the priority.

Inside life.

I remember going to one Bureau, and the man looked at me and shook his head. He said, “If you had come under the last government, you would have had a job by tomorrow. But look,” then he brought out a list. 40 people. “These are the people I’m supposed to assimilate into my jurisdiction, and I don’t even have the need for 10 people.”

I said, oya let me work for free. He said, “I don’t even have space for you to sit down.”

Case closed. What did you do for the one year?

I started writing. I really had nothing else to do.

I’m trying to draw a straight line from this writing to how food entered your mouth. Help me out.

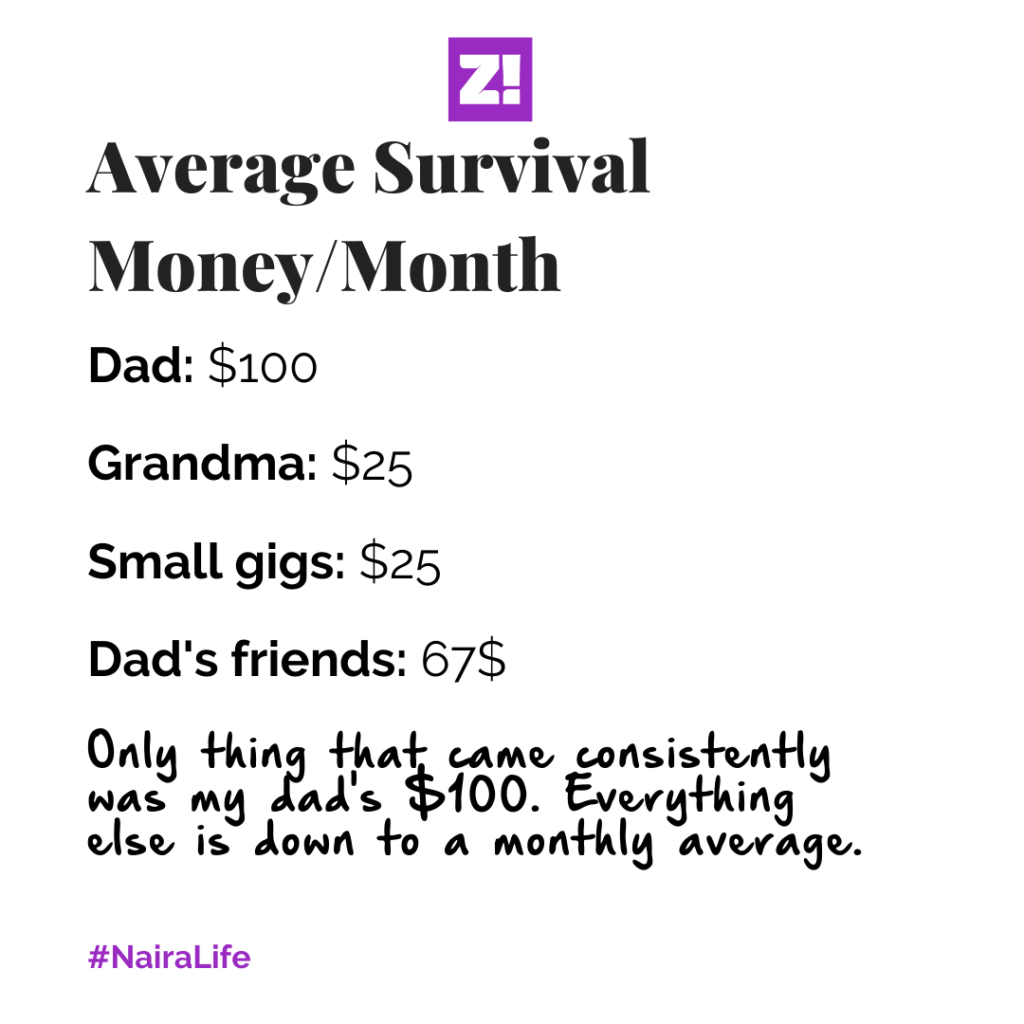

Ah, my father sent me money every month, since he’s the chief supporter of me coming back to Liberia – he’s not in the country, by the way. He helps his boy, as my boss meh. I started helping people research whatever they were working on, for school or work – about six in total. Also, my father has plenty friends, so when I first came back, all those “Ah how are you?” handouts helped a lot.

How did you end your job drought?

My dad came visiting for something else, but it was a good time to have a sitdown. And he went, “You’ve been here for a whole year, and nothing’s happening. Your mother and I have been thinking, and we’ve concluded that we don’t have $100 to be giving you every month.”

I mean, I understood what he was saying. He’s always had lots of mouths to feed. Every Liberian family fortunate enough, definitely has a lot of mouths to feed. Not like he’s a rich a man.

By the end of the conversation, we settled on a February deadline for my last $100.

My uncles said I came at the wrong time. “When Ellen was here,” they’d say, “there were a lot of NGOs and International Organisations.”

Back to your dad’s deadline. How did that go?

I somehow managed to get a teaching job. I wanted to teach at the Government University, that would have paid me like $300-400 per month. The process was taking too long. Another Private University I applied to gave me an offer, and I was hired.

Also, I applied for an internship at an NGO, and got that. My job there was to work with them in documenting stories of change in Liberia, and it felt good to be part of that. Because of this, I actually made up my mind that I was going to teach for only one session, so that I could perhaps, end up working full time for the NGO.

So, I was teaching thrice a week, one hour on each day. I was getting paid $120. Then the NGO is paying $150.

I freelanced on small research projects too, but it hasn’t come consistently, or paid significantly enough for me to really think of it as a proper source of income. It’s fetched only about $300 this year.

Oh wait, another window opened.

What?

Remember when we talked about Law School? I got admitted, so it was extra incentive to leave the teaching job. That’s costing $1500 per semester for tuition, but my parents are covering that.

2019 looks super packed and busy! And you’re juggling this with the NGO?

Yeah. Although, my current contract with the NGO just expired. We’re currently negotiating new terms, and that might pay me between $300-$500, hopefully.

What are your running costs these days?

Tithe: $50

Data: $30

Transport and stuff: $30 x 4

Obligations: $50

I’m curious, what does $500 fetch you in a city like Monrovia

It’s decent. The place I want to get for example is in an estate. It’ll be a two or three-bedroom apartment and I’ll be spending about $150-$200 every month on rent, if they don’t ask for a six-month advance that is. Most people I know pay their rent on a monthly basis.

There are apartments that go for up to $1500 per month, fully furnished. Those ones tend to go to the expatriates, and there are a lot of them in Monrovia.

Also, food is not expensive here. I asked my aunty, and she said $25 is enough to cook Jollof Rice for 5 people. Keep in mind that the portions are larger here, and it’s generally richer that y’all’s Jollof. There’s meat, fish –

– Let’s be civil, please.

Hahaha.

Talking about expatriates, I haven’t heard you mention the Liberian Dollar since we started talking.

Yeah, we juggle the two currencies. If you’re working for the U.N. for example, how often do you have to interact with the Liberian Dollar? You’re not buying Pure Water or food for Lapper-Be-Door –

Lapper be what?

Wrapper. Be. Door. It’s like Bukas in Nigeria. They call it that here because most of them have wrappers as doors.

Ohhhh.

So yes, there are people in Liberia that rarely use the Liberian dollar.

How are salaries paid then?

Some places give you in LD, some pay 50% LD, 50% USD. Government pays roughly between the two currencies. The USD is generally more stable to be paid in.

Talking about stability, how unstable is the LD?

It just became unstable two years ago. Before, it was plugged at 100. At the beginning of 2019, it wasn’t even up to 200. Now it’s 210 to the USD. People live in the country with two currencies.

I actually gathered some of my thoughts about it here. What do you think?

It’s amusing how strange it is to you. This is how it has always been in Liberia. And there’s a long Americo-Liberia history about it that we can’t even digress to right now.

How much do you imagine you’d be earning five years?

Over a $1000 for sure. I’d be working with an international NGO, with a Law Degree. The good thing is, I’m schooling and working. So I’m building my work experience while getting another degree.

You keep talking about NGOs.

Yes, those are some of the most aspirational jobs here. And then the government. During Ellen’s government, salaries and benefits were huge. Now, it’s mostly cost cutting. Even some of the NGOs have left. But I still want to work in government. I feel like there’s only so much impact you can make from the outside.

Another thing is, Liberia doesn’t have that big of a private sector.

How do you use money here?

I just put it in my wallet. I haven’t gotten an ATM, because I don’t need it.

Is that just you or it’s a Liberian thing?

I think it’s a mixture of both. Because most places you’re going to buy things, there’s no POS. The only reason I’d eventually get an ATM is so I don’t have to queue at the bank. Then there’s also mobile money.

About you now, how would you rate your financial happiness? Over 10?

Three because I could be making more money, but this is the part where I take a small step back, so I can make more money in the future. Because I’m trying to get a law degree full time – it’s three years here – I can’t give work the full time attention it should be getting.

So every time I think about it, I just tell myself, a little patience, man. A little patience.

This conversation was had over lunch at a restaurant in Monrovia in Monrovia a few weeks ago, while on the JollofRoad. The best part? Food was paid for with my Nigerian account; A scan from my app. And pim pim, done. It’s Ecobank Pay.